Volume 11, Issue 3 (12-2023)

Jorjani Biomed J 2023, 11(3): 6-8 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Farmanbordar E, Badeleh Shamushaki M T. Fear of body image in women: comparison of Fars and Turkmen ethnicities. Jorjani Biomed J 2023; 11 (3) :6-8

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-999-en.html

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-999-en.html

1- . Department of Clinical Psychology, Bandar-e-Gaz Azad University, Iran

2- Department of Health Psychology, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran ,badeleh@gmail.com

2- Department of Health Psychology, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 386 kb]

(2919 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (7811 Views)

Full-Text: (1546 Views)

Introduction

Hypothetically, women are dissatisfied with their bodies due to the upward social comparison by which they have a feeling of inadequacy. Studies show that women strive to change their bodies in order to compensate for this deficiency (1). In line with the results of many studies, statistics have shown a dramatic increase in cosmetic surgery among women in the 21st century (2). This indicates that women experience a lot of dissatisfaction with their body size and shape (3). The degree of this dissatisfaction depends on ideal body image, and several studies have shown that beauty and social priority for women are synonymous with having a slim figure (4). Since this ideal is almost unattainable for most women, the idealization of a slender body directly reinforces body dissatisfaction (5). In another study, many women experienced dissatisfaction with their bodies as negative consequences that influenced other important aspects of their lives, including their professional, social, and intimate relationships (6). In addition, the body image can be described as a multifaceted structure that involves a person's perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and actions toward his or her body, especially appearance (7).

According to some researchers (8-10), the term body image consists of several constructs, including satisfaction (dissatisfaction) with weight, satisfaction (dissatisfaction) with the body, body shame, appearance (dis)satisfaction, appearance evaluation, body appreciation, body dysmorphia, and body schema. The factors that contribute to body image dissatisfaction are the sociocultural pressures that make women have a lean body as an ideal body (11). This is largely due to the cultures in which slimness is portrayed in all media (12).

Since the concept of the body depends on the context of cultural and social groups, women with different ethnic and racial backgrounds may differ in the degree of dissatisfaction with their bodies (13). Ethnic identity may protect individuals from thin or ideal internalization, weight concerns, and eating concerns because values and ideals of appearance vary widely among different ethnic groups (14). In the same vein, African-American women are less likely to suffer from being overweight, and they are probably satisfied with having a larger body than European and American women (15). However, pressures from social media have changed this view and have created an ideal and slimmer figure for women living in non-Western societies that have undergone rapid socioeconomic changes (16). On the other hand, the results of a study demonstrate that women who feel extra pressure to achieve the ideal body image for social approval may have a sense of shame and fear of being seen as imperfect, lowly, and unattractive by others (17).

The role of sex in body image has been confirmed, and especially body image dissatisfaction is significantly higher in women. The research on the factors affecting the levels of dissatisfaction with body image shows that racial differences in women have received more attention, while few studies have focused on ethnic differences and have had contradictory results. Despite the presence of different ethnicities in Iran, the number of studies to assess the fear of body image among different ethnicities is scant. Therefore, we decided to study the fear of body image among Fars and Turkmen women.

Methods

Participants

The study population of this descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study was Fars and Turkmen women living in Gonbad, Iran, in 2020. The sample size (N = 372) was determined by Krejcie and Morgan's Table, and the participants were recruited via convenience sampling. It should be noted that the present study was conducted in compliance with all ethical principles and confidentiality.

Measures

Demographic checklist: It included information such as age, marital status, education, occupation, income level, mother tongue, place of residence (city or village), and the amount of internet usage.

Littleton's Body Image Concern Inventory: This inventory was first designed and validated by Littleton et al. (2005). It consists of 19 items on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The score ranges from 19 to 95 (higher scores indicate higher dissatisfaction), with a total reliability of 93%. In Iran, Basaknejad and Ghaffari (2007) reported a 95% validity for this inventory (18), and Heidari et al. (2016) reported a 78% reliability for it (19).

Data analysis

To analyze the data, we used descriptive (mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, t test, and Pearson's correlation coefficient) in SPSS v. 17 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

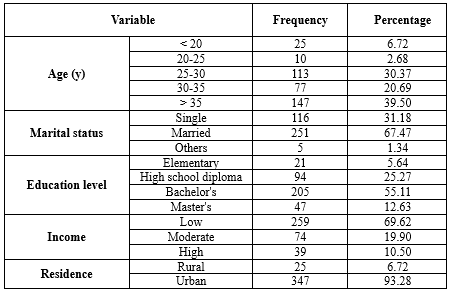

Table 1 shows that the lowest frequency of the respondents was in the range of 20-25 years (2.66%), and the highest one belonged to those over 35 years (38.70 %). Of the total participants, 68.81% were married, and 31.19% were single. The most frequent level of education was a bachelor's degree (55.64%), and the least frequent was a high school diploma (5.64%). In terms of employment, most participants were homemakers (32.80%), official clerks (30.91%), self-employed (20.16%), or unemployed (16.12 %). Regarding ethnicity, 49.5% of the participants were Fars, and 50.5% of them were Turkmen.

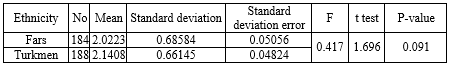

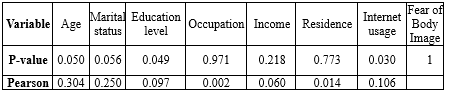

To check the normality of the data, we used the Kolmogorov-Simonov test, and the results suggested no apparent violation of the assumption (P = .112). Therefore, the distribution was normal, and we used parametric tests. As shown in Table 2, the fear of body image was not significantly different between Fars and Turkmen ethnicities. Furthermore, the results of Table 3 show that the variables of age, education level, and internet usage were related to the variable of body image.

Discussion

In this research, we assessed the relationship between ethnicity and the fear of body image. The results showed that ethnicity does not make a difference in the fear of body image. In other words, there is no difference in the fear of body image between Fars and Turkmen women, yet the results showed that age, education level, and internet usage correlated with the fear of body image.

It has always been assumed that there may be different ideals about body image in different ethnic groups that are passed down from generation to generation. Testing of this hypothesis in different experimental studies has shown different results (20). In agreement with our study, a researcher reported that there was no relationship between women's ethnic identities and their body dissatisfaction (21). However, the results of some research were inconsistent with the findings of the present study (22-25). They indicate that membership in ethnic groups does not change the awareness and acceptance of body image standards. In addition, Ricciardelli et al. (2007), in their study of body image concerns and eating disorders among women in ethnic groups, emphasized that researchers need to keep in mind the existence of diversity between individuals in a particular group, as well as significant differences between ethnic groups (26).

Currently, it is said that ethnic identity can help women not to accept the values that the media (internet, television, magazines, advertising, and video games) offer about the perfect slim body. Meanwhile, the results of some studies suggest that ethnicity may not be the most prominent or distinguishing factor in making various images of the body (27). In agreement with the present study, Rakhkovskaya et al. (2014), in confirming the role of the media, showed that exposure to the environment and the factors that reflect certain ideals of body image can be a risk factor for creating a negative body image (14). According to the theory of social comparison, women consider the ideal media images as a point of comparison to improve the current shape of their bodies (28).

Based on a study, ethnicity-related factors such as the level of culture, self-esteem, or economic and social status can act as a real risk or protective factor. Furthermore, standard measurements of body image may be culturally biased, and they may not take into account the culturally beautiful standards that women have (27). The importance of ethnicity for individuals' social identity may be enhanced by access to the cultural meaning that is inherent in shared habits, shared sense of history, or group norms, which in turn can increase self-esteem and positive self-assessment (29). In general, the literature and research results in this field are contradictory, and the ability to draw strong conclusions and analyses about the effects of ethnicity is limited.

Despite the growing research on body image, the studies related to body dissatisfaction and socioeconomic status (SES) are limited (30), and one of the commonly used measures is education (31). Thus, in our study, we examined the association between fear of body image and education. In line with our result, Rosenqvist et al (31) and Cheung et al (32) confirmed the relationship between fear of body image and education level.

Consistent with our study, we can mention the result of other research that verifies the relationship between body image and age (33,34). Furthermore, some research highlighted that body dissatisfaction, weight anxiety, attempts to lose or gain weight, and some unhealthy eating patterns may begin in the pre-pubertal period and increase after puberty, especially in women (35). In addition, the effect of aging cannot be fully captured in cross-sectional studies; there has been a call for longitudinal cohort studies of body image to better control the effect of historical changes in body ideals.

In addition to showing contradictory results, some studies that are similar to the present study show that dissatisfaction with body image has been studied more between different cultural groups and races. Although some people are concerned that the emphasis on ethnicity may be socially divisive, others argue that ethnicity can be an important source of graceful characteristics, and they call for empirical studies that are in terms of the role of ethnicity in human development (36). As a result, we suggest that some similar research be conducted on different ethnicities. The present study is limited due to the consideration of women in only 2 ethnic groups (Fars and Turkmen). Therefore, we should be cautious in extending the results to other ethnicities and to males.

Conclusion

In spite of belonging to an ethnic group, women seem to be influenced more by the prevailing norms of society. These norms always put significant social pressures on women to maintain their youthful features and ideal body image, which undoubtedly affects their perception of their body image and self-criticism. The findings of this study provide valuable insight into body image fear among Fars and Turkmen women; thus, it can be concluded that the role of ethnicity in body image fear is different.

Limitations

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of the Islamic Azad University, Bandar-e-Gas Branch, and all the women participating in this study.

Funding sources

This study was not financially supported.

Ethical statement

This article is a report of the master's thesis in clinical psychology approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Bandar-e-Gas Branch, with the dissertation code 4042921223916011398178901. All ethical principles (obtaining informed consent from participants and the confidentiality of information) were observed.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki; Data collection: Elmira Farmanbordar; Data analysis: Elmira Farmanbordar; Drafting of the manuscript: Elmira Farmanbordar, Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki; Critical revision of the manuscript: Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki

Hypothetically, women are dissatisfied with their bodies due to the upward social comparison by which they have a feeling of inadequacy. Studies show that women strive to change their bodies in order to compensate for this deficiency (1). In line with the results of many studies, statistics have shown a dramatic increase in cosmetic surgery among women in the 21st century (2). This indicates that women experience a lot of dissatisfaction with their body size and shape (3). The degree of this dissatisfaction depends on ideal body image, and several studies have shown that beauty and social priority for women are synonymous with having a slim figure (4). Since this ideal is almost unattainable for most women, the idealization of a slender body directly reinforces body dissatisfaction (5). In another study, many women experienced dissatisfaction with their bodies as negative consequences that influenced other important aspects of their lives, including their professional, social, and intimate relationships (6). In addition, the body image can be described as a multifaceted structure that involves a person's perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and actions toward his or her body, especially appearance (7).

According to some researchers (8-10), the term body image consists of several constructs, including satisfaction (dissatisfaction) with weight, satisfaction (dissatisfaction) with the body, body shame, appearance (dis)satisfaction, appearance evaluation, body appreciation, body dysmorphia, and body schema. The factors that contribute to body image dissatisfaction are the sociocultural pressures that make women have a lean body as an ideal body (11). This is largely due to the cultures in which slimness is portrayed in all media (12).

Since the concept of the body depends on the context of cultural and social groups, women with different ethnic and racial backgrounds may differ in the degree of dissatisfaction with their bodies (13). Ethnic identity may protect individuals from thin or ideal internalization, weight concerns, and eating concerns because values and ideals of appearance vary widely among different ethnic groups (14). In the same vein, African-American women are less likely to suffer from being overweight, and they are probably satisfied with having a larger body than European and American women (15). However, pressures from social media have changed this view and have created an ideal and slimmer figure for women living in non-Western societies that have undergone rapid socioeconomic changes (16). On the other hand, the results of a study demonstrate that women who feel extra pressure to achieve the ideal body image for social approval may have a sense of shame and fear of being seen as imperfect, lowly, and unattractive by others (17).

The role of sex in body image has been confirmed, and especially body image dissatisfaction is significantly higher in women. The research on the factors affecting the levels of dissatisfaction with body image shows that racial differences in women have received more attention, while few studies have focused on ethnic differences and have had contradictory results. Despite the presence of different ethnicities in Iran, the number of studies to assess the fear of body image among different ethnicities is scant. Therefore, we decided to study the fear of body image among Fars and Turkmen women.

Methods

Participants

The study population of this descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study was Fars and Turkmen women living in Gonbad, Iran, in 2020. The sample size (N = 372) was determined by Krejcie and Morgan's Table, and the participants were recruited via convenience sampling. It should be noted that the present study was conducted in compliance with all ethical principles and confidentiality.

Measures

Demographic checklist: It included information such as age, marital status, education, occupation, income level, mother tongue, place of residence (city or village), and the amount of internet usage.

Littleton's Body Image Concern Inventory: This inventory was first designed and validated by Littleton et al. (2005). It consists of 19 items on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The score ranges from 19 to 95 (higher scores indicate higher dissatisfaction), with a total reliability of 93%. In Iran, Basaknejad and Ghaffari (2007) reported a 95% validity for this inventory (18), and Heidari et al. (2016) reported a 78% reliability for it (19).

Data analysis

To analyze the data, we used descriptive (mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, t test, and Pearson's correlation coefficient) in SPSS v. 17 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows that the lowest frequency of the respondents was in the range of 20-25 years (2.66%), and the highest one belonged to those over 35 years (38.70 %). Of the total participants, 68.81% were married, and 31.19% were single. The most frequent level of education was a bachelor's degree (55.64%), and the least frequent was a high school diploma (5.64%). In terms of employment, most participants were homemakers (32.80%), official clerks (30.91%), self-employed (20.16%), or unemployed (16.12 %). Regarding ethnicity, 49.5% of the participants were Fars, and 50.5% of them were Turkmen.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

|

|

Table 2. Statistical analysis of body image fear using a t test

|

|

Table 3. The relationship between body image fear and demographic variables

|

Discussion

In this research, we assessed the relationship between ethnicity and the fear of body image. The results showed that ethnicity does not make a difference in the fear of body image. In other words, there is no difference in the fear of body image between Fars and Turkmen women, yet the results showed that age, education level, and internet usage correlated with the fear of body image.

It has always been assumed that there may be different ideals about body image in different ethnic groups that are passed down from generation to generation. Testing of this hypothesis in different experimental studies has shown different results (20). In agreement with our study, a researcher reported that there was no relationship between women's ethnic identities and their body dissatisfaction (21). However, the results of some research were inconsistent with the findings of the present study (22-25). They indicate that membership in ethnic groups does not change the awareness and acceptance of body image standards. In addition, Ricciardelli et al. (2007), in their study of body image concerns and eating disorders among women in ethnic groups, emphasized that researchers need to keep in mind the existence of diversity between individuals in a particular group, as well as significant differences between ethnic groups (26).

Currently, it is said that ethnic identity can help women not to accept the values that the media (internet, television, magazines, advertising, and video games) offer about the perfect slim body. Meanwhile, the results of some studies suggest that ethnicity may not be the most prominent or distinguishing factor in making various images of the body (27). In agreement with the present study, Rakhkovskaya et al. (2014), in confirming the role of the media, showed that exposure to the environment and the factors that reflect certain ideals of body image can be a risk factor for creating a negative body image (14). According to the theory of social comparison, women consider the ideal media images as a point of comparison to improve the current shape of their bodies (28).

Based on a study, ethnicity-related factors such as the level of culture, self-esteem, or economic and social status can act as a real risk or protective factor. Furthermore, standard measurements of body image may be culturally biased, and they may not take into account the culturally beautiful standards that women have (27). The importance of ethnicity for individuals' social identity may be enhanced by access to the cultural meaning that is inherent in shared habits, shared sense of history, or group norms, which in turn can increase self-esteem and positive self-assessment (29). In general, the literature and research results in this field are contradictory, and the ability to draw strong conclusions and analyses about the effects of ethnicity is limited.

Despite the growing research on body image, the studies related to body dissatisfaction and socioeconomic status (SES) are limited (30), and one of the commonly used measures is education (31). Thus, in our study, we examined the association between fear of body image and education. In line with our result, Rosenqvist et al (31) and Cheung et al (32) confirmed the relationship between fear of body image and education level.

Consistent with our study, we can mention the result of other research that verifies the relationship between body image and age (33,34). Furthermore, some research highlighted that body dissatisfaction, weight anxiety, attempts to lose or gain weight, and some unhealthy eating patterns may begin in the pre-pubertal period and increase after puberty, especially in women (35). In addition, the effect of aging cannot be fully captured in cross-sectional studies; there has been a call for longitudinal cohort studies of body image to better control the effect of historical changes in body ideals.

In addition to showing contradictory results, some studies that are similar to the present study show that dissatisfaction with body image has been studied more between different cultural groups and races. Although some people are concerned that the emphasis on ethnicity may be socially divisive, others argue that ethnicity can be an important source of graceful characteristics, and they call for empirical studies that are in terms of the role of ethnicity in human development (36). As a result, we suggest that some similar research be conducted on different ethnicities. The present study is limited due to the consideration of women in only 2 ethnic groups (Fars and Turkmen). Therefore, we should be cautious in extending the results to other ethnicities and to males.

Conclusion

In spite of belonging to an ethnic group, women seem to be influenced more by the prevailing norms of society. These norms always put significant social pressures on women to maintain their youthful features and ideal body image, which undoubtedly affects their perception of their body image and self-criticism. The findings of this study provide valuable insight into body image fear among Fars and Turkmen women; thus, it can be concluded that the role of ethnicity in body image fear is different.

Limitations

- The data are related to women living in a city located in the north of Iran, which may be different from elsewhere.

- The religious affiliation of the samples is not homogeneous and can have a different effect on the fear of body image.

- Demographic variables such as physical activity and diet were not assessed.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of the Islamic Azad University, Bandar-e-Gas Branch, and all the women participating in this study.

Funding sources

This study was not financially supported.

Ethical statement

This article is a report of the master's thesis in clinical psychology approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Bandar-e-Gas Branch, with the dissertation code 4042921223916011398178901. All ethical principles (obtaining informed consent from participants and the confidentiality of information) were observed.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki; Data collection: Elmira Farmanbordar; Data analysis: Elmira Farmanbordar; Drafting of the manuscript: Elmira Farmanbordar, Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki; Critical revision of the manuscript: Mohammad Taghi Badeleh Shamushaki

Type of Article: Original article |

Subject:

Health

Received: 2023/11/18 | Accepted: 2023/12/11 | Published: 2023/12/19

Received: 2023/11/18 | Accepted: 2023/12/11 | Published: 2023/12/19

References

1. Pedalino F, Camerini L. Instagram Use and Body Dissatisfaction: The Mediating Role of Upward Social Comparison with Peers and Influencers among Young Females. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1543. Int J Environ Res & Public Health. 19(3). [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Qureshi MA, Bashir MA, Ghayas S, Ansari J. Ideal Body Image and Women's Psychology: A Systematic Review. KASBIT Business Journal. 2021;14(1):23-42. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

3. Sarwer, DB. Body image, cosmetic surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. Body Image. 2019;31:302-308. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Wang K, Liang R, Yu X, Shum DH, Roalf D, Chan RC. The thinner the better: Evidence on the internalization of the slimness ideal in Chinese college students. PsyCh journal. 2020;9(4):544-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Thompson JK, Stice E. Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current directions in psychological science. 2001;10(5):181-3. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

6. Donaghue N. Body satisfaction, sexual self-schemas and subjective well-being in women. Body Image. 2009;6(1):37-42. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Cash TF, Szymanski ML. The development and validation of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of personality assessment. 1995;64(3): 466-77. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Rodgers RF, Laveway K, Campos P, de Carvalho PHB. Body image as a global mental health concern. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2023;10:e9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Mills JS, Minister C, Samson L. Enriching sociocultural perspectives on the effects of idealized body norms: Integrating shame, positive body image, and self-compassion. Front Psychol. 2022;13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Engel MM, Woertman EM, Dijkerman HC, Keizer A. Functionality appreciation is associated with improvements in positive and negative body image in patients with an eating disorder and following recovery. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:179. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Mediators of the relationship between media literacy and body dissatisfaction in early adolescent girls: Implications for prevention. Body Image. 2013;10(3):282-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Frayon S, Cavaloc Y, Wattelez G, Cherrier S, Touitou A, Zongo P, et al. Body image, body dissatisfaction and weight status of Pacific adolescents from different ethnic communities: a cross-sectional study in New Caledonia. Ethnicity & health. 2020;25(2):289-304. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Crago M, Shisslak CM. Ethnic differences in dieting, binge eating, and purging behaviors among American females: A review. Eating disorders. 2003;11(4):289-304. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Rakhkovskaya LM, Warren CS. Ethnic identity, thin-ideal internalization, and eating pathology in ethnically diverse college women. Body Image. 2014;11(4):438-45. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Robinson SA, Webb JB, Butler-Ajibade PT. Body image and modifiable weight control behaviors among black females: a review of the literature. Obesity. 2012;20(2):241-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Levine MP, Santos JS. Beauty-Cosmetic Science, Cultural Issues and Creative Developments. 2021. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

17. Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J. Self-defining memories of body image shame and binge eating in men and women: Body image shame and self-criticism in adulthood as mediating mechanisms. Sex Roles. 2017;77(5):338-51. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

18. Bassaknezhad S, Ataie Moghanloo V, Mehrabizadeh honarmand M. The effectiveness of puberty mental health training on fear of body image and adjustment in high school male students. J Research Health. 2013;3(1):269-77. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

19. Heidari M, Eskandari sabzi H, Nezarat S, Mojadam M, Sarvandian S, Shabani S, et al. An analytical survey on the fear of body image and aggression in girl and boy high school students. Nursing And Midwifery Journal. 2017;14(10):837-46. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

20. Chapa S, Jordan Jackson FF, Lee J. Antecedents of ideal body image and body dissatisfaction: The role of ethnicity, gender and age among the consumers in the USA. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing. 2020;11(2):190-206. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

21. Baugh E, Mullis R, Mullis A, Hicks M, Peterson G. Ethnic identity and body image among Black and White college females. Journal of American College Health. 2010;59(2):105-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in body image development among college students. Body Image. 2012;9(1):126-30. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Dabros JL. Correlates of body image of undergraduate females attending Andrews University. Andrews University. 2014. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

24. Winter VR, Danforth LK, Landor A, Pevehouse-Pfeiffer D. Toward an understanding of racial and ethnic diversity in body image among women. Social Work Research. 2019;43(2):69-80. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

25. Satghare P, Mahesh MV, Abdin E, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. The relative associations of body image dissatisfaction among psychiatric out-patients in Singapore. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5162. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Williams RJ, Thompson JK. The role of ethnicity and culture in body image and disordered eating among males. Clinical psychology review. 2007;27(5):582-606. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Thomas A. Relationship between Body Image and Self-Esteem Among Adolescents in Mysuru (July 20, 2023). Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR). 2023;10(7):f219-25. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

28. Frisby CM. Does race matter? Effects of idealized images on African American women's perceptions of body esteem. Journal of Black Studies. 2004;34(3):323-47. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

29. Abrams LS, Stormer CC. Sociocultural variations in the body image perceptions of urban. adolescent females. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31(6):443-50. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

30. Grogan S. Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. Routledge; 2021. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

31. Rosenqvist E, Konttinen H, Berg N, Kiviruusu O. Development of Body Dissatisfaction in Women and Men at Different Educational Levels During the Life Course. Int J Behav Med. 2023:1-12. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

32. Cheung YTD, Lee AM, Ho SY, Li ETS, Lam TH, Fan SYS, et al. Who wants a slimmer body? The relationship between body weight status, education level and body shape dissatisfaction among young adults in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1-10. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Nishizawa Y, Kida K, Nishizawa K, Hashiba S, Saito K, Mita R. Perception of self‐physique and eating behavior of high school students in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2003;57(2):189-96. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Gruszka W, Owczarek AJ, Glinianowicz M, Bąk-Sosnowska M, Chudek J, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M. Perception of body size and body dissatisfaction in adults. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1159. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Wang Z, Byrne NM, Kenardy JA, Hills AP. Influences of ethnicity and socioeconomic status on the body dissatisfaction and eating behaviour of Australian children and adolescents. Eating behaviors. 2005;6(1):23-33. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

36. Spencer MB, Markstrom‐Adams C. Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child dev. 1990;61(2):290-310. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |